Irish President's speech at state dinner in honour of top Vietnamese leader

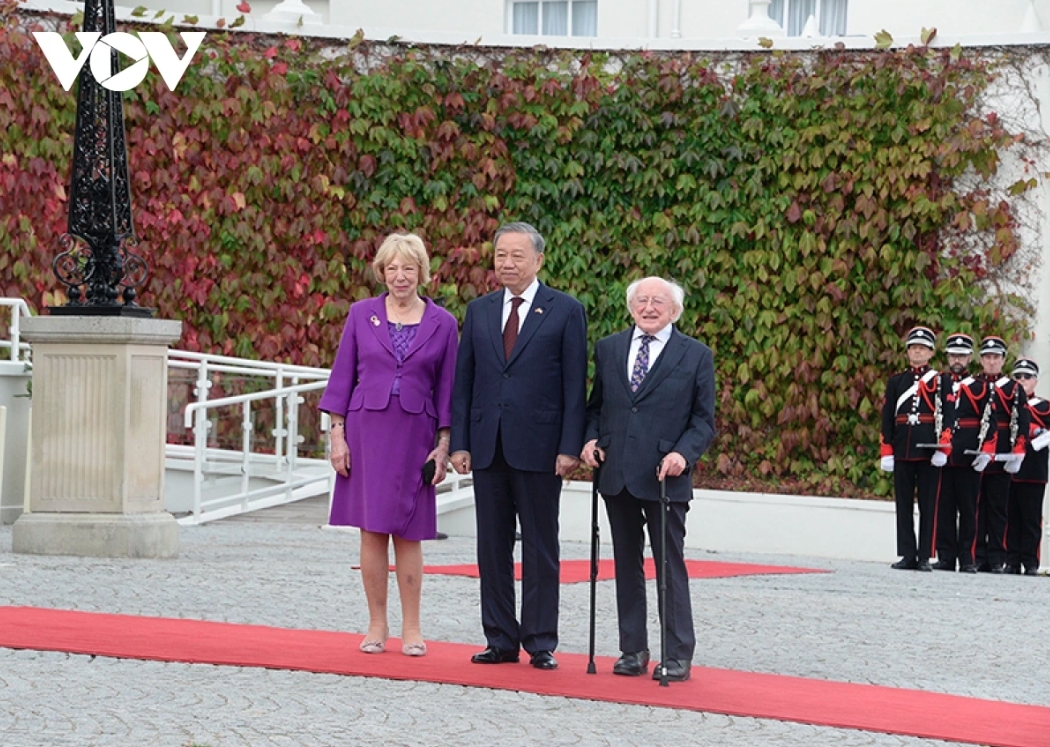

Irish President Michael D. Higgins delivered a speech at a state dinner in Dublin on October 2 in honour of General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam Central Committee and State President To Lam on the occasion of the top Vietnamese leader's state visit to Ireland.

The following is the full text of the speech.

Speech by President Michael D. Higgins

At a State Dinner in Honour of the State Visit of the President of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam To Lam

Áras an Uachtaráin

Wednesday, 2nd October 2024

Your Excellency President To Lam,

Tánaiste,

Ministers,

Ambassadors,

Distinguished guests,

A cháirde,

Fíor-chaoin fáilte romhaibh uilig agus go speisialta roimh Uachtarán Vítneam agus iad ag taistil leis.

It is my great pleasure to welcome you this evening to Áras an Uachtaráin, home of all Irish Presidents since 1938, and to have the opportunity to repay the kind hospitality that Sabina and I were afforded in 2016 when we travelled to your great and very beautiful country, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

It was a great honour to be the first Irish President to make a State Visit to Vietnam. It was my hope for that occasion that my visit then would contribute to the sustaining and deepening of the true and growing friendship that unites the peoples of Ireland and Vietnam.

I am certain that this visit which you make now to Ireland will develop and extend this relationship even more strongly.

I recall our visit to your ethnic communities where some of Irish Agencies work.

That this is the first State Visit from Vietnam to Ireland makes it an even greater occasion and opportunity to reflect and renew the bonds of friendship between our two countries. I was saddened to receive news that your wife Madame Ngo Phuong Ly [Ngo Foo-ong Lee] would not be travelling with due to illness. May I wish Madame Ngo Phuong Ly a speedy recovery to full health.

May I take this occasion to express solidarity with you, President, and through you, to the people of Vietnam on the tragic loss of life and devastating impacts of Typhoon Yagi. On behalf of the people of Ireland, I extend my deepest sympathies to the families and communities impacted by the typhoon's destruction. As a long-standing development partner for Vietnam, Ireland is committed to supporting the humanitarian recovery effort.

I further extend my sincere condolences on the still recent passing of General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong [Nu-wen Foo Chom]. During my visit to Vietnam in 2016, I met with General Secretary Trong. He was a figure of international significance, who made an immense contribution to Vietnam.

May I suggest that our two nations, Vietnam and Ireland, share so much experience in our respective histories. There are so many ways in which we Irish can identify, in sympathy and imagination, with the Vietnamese people's aspirations for independence and the right to achieve fulfilment with respect for one's own culture.

Ireland's journey and the journey of Vietnam are journeys that strike a chord. Yours is a history of so much inflicted suffering by external powers. While that history must not disable e your present, or deprive you of future possibilities, it would be so important not to assume some false amnesia with regard to its consequences. Your history in its fullness belongs to you, and the world must learn from its imposed tragedies.

Indeed the images of the brutality of war from Vietnam - I think of the posters of the war from Vietnam - had a huge effect on civil rights' struggles all over the world.

Both our cultures have their roots in ancient civilisations renowned for the value they placed on scholarship, spiritual cultivation and the arts. Both our peoples have endured the harmful experience of the imposition of a perceived superiority of a hegemonic culture, of empire, and, in your case, the ambitions of four imperialisms. Both have suffered from the scourge of famine and its profound and many consequences.

Both of our nations have suffered, in cultural terms, from imperialist theories of culture which sought to justify the racial superiority of the coloniser over the colonised, and to rationalise the ruling of the world, not by the many in their diversity, but by a handful of imperial powers.

Both our peoples have led an unyielding and irrepressible struggle for independence which has involved meetings in Paris. We recall the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, after that collision of Empires that the First World War constitutes; a conference to which a young Ho Chi Minh sent a petition asking for the delivery of the independence that had been promised from France. So many of our contemporary conflicts are the fruit of an unfinished end to such empires. Ho Chi Minh was not alone in not receiving an answer from the presiding world powers.

Similarly, the doors in Paris remained shut to Irish Republicans who travelled there attempting to garner support for the cause of independence from the British Empire. Both rejections were perceived by the Irish and Vietnamese leaders of the time as proof of the risks of placing an excessive trust in concessions from an imperial power.

Vietnam and Ireland understand only too well how difficult it can be to secure, vindicate and deliver on the promises of freedom, justice and equality that motivated and were invoked for the struggle for independence. The decades following the heady atmosphere of the days of declared independence are the most challenging.

This historical affinity we share gives us not only a common understanding of the impacts of colonialism and conflict, but of the tasks of state construction and the meeting of citizens' demands, and continues to resonate in our relationship at all levels. In recent decades, our two countries have travelled on a challenging, but rewarding, journey from conflict to fruitful, harmonious relations with those who are the successors of our past oppressors. Both of our countries appreciate the value of peace and stability in a turbulent world.

On matters of economy, both Ireland and Vietnam have rapidly moved from being dependent on relatively poor agrarian economies to more diversified forms of economic production and achieving significant social and economic advances in a complex, globalised world, that is ever more interdependent, and not just on matters of trade, yet one that has created global issues in relation to, for example, the impact of climate change.

It is a world that now requires a new and imaginative global multilateral architecture if it is to achieve a diversified democratic future, one that can deliver a newer connection between social rights, economy and ecology.

Vietnam is to be commended for its achievements in reducing poverty, improving educational access and improving infrastructure. Where thirty years ago, up to 60 percent of the Vietnamese population lived in poverty, the rate of multidimensional poverty is now below 4 percent.

This remarkable achievement, guided by a commitment to the United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals, has transformed the lives and prospects of tens of millions of people. During my visit, I saw first-hand how the energy and dynamism of your people has made this progress possible. Such achievements constitute little less than a shared social wealth.

Ireland's approach to Official Development Assistance over the decades has been informed by Ireland's own experience of famine and underdevelopment. We have therefore prioritised support for food security as part of our development assistance programme. In Vietnam, this is reflected in the Ireland Vietnam Agrifood Partnership, which is supporting climate-resilient primary production, food systems transformation and cooperative development.

I know that Vietnam is particularly interested in Ireland's cooperative movement, a movement that promoted economic democracy against the backdrop of sweeping political change that led to independence more than a century ago. New global challenges have reminded us that perhaps it is worth exploring once again how we might build a more co-operative economy for a flourishing, inclusive and sustainable existence together.

In recent decades, Vietnam and Ireland have experienced a mutually beneficial trade and investment relationship. With rapid changes and new opportunities have also come tremendous new challenges, particularly with regards to the globalised economic and trade structures to which Vietnam and Ireland have been opening.

Such structures involve risk that emphasises the importance of transparency and accountability and raise serious questions, in particular with the rise of so many unaccountable, inappropriate development models and a democratic deficit which, taken together, is resulting in a legitimation crisis that German philosopher Jürgen Habermas first wrote of some 50 years ago.

Everywhere we can see how deepening inequality and poverty threaten social cohesion, how climate change, food security, global poverty and migration are inextricably linked, fuelling displacement and conflict, and how inter-generational justice is threatened as we witness our natural environment degrading at an alarming pace - what one might term a species failure.

Vietnam's role as one of only four countries globally to enter the EU-supported Just Energy Transition Partnership shows a determination to confront and lead in the global response to climate change, aiming as it does to transform Vietnam's renewable energy capability. Through responding to and adopting international initiatives like this, I am confident that as a global community we can meet the challenges that face us.

Those who speak for states must now also speak to what are global issues. We are living through a period when militarism has replaced diplomacy. We have been told that we may be at the beginning of a new nuclear armaments race. Certainly, the statistics corroborate this: last year, global military expenditure increased by 6.8% to US$2.44 billion, the highest ever recorded.

We must confront both the shallowness and false inevitabilities of such a militaristic discourse. I suggest that we must never lose sight of the possibilities that remain for us in the pursuit of conditions of a shared peace; how our lives could be liberated without war, famine, hunger and greed in a just world that shuns the poisonous ideals of imperialism, racism and 'Othering' and embraces the decent instincts of humanity; how we can build a society of inclusion at home, while working together with other nations to build a peaceful, sustainable, and hopeful world.

I take this opportunity to commend the significant and positive role played by Vietnam in regional security, including its non-aligned diplomatic approach and 'Four Nos' policy-no military alliances, no siding with one country to act against another, no foreign military bases or using Vietnam as leverage to counteract other countries, and no threat or use of force. This non-alignment strategy and healthy, balanced relations with major powers has served Vietnam well.

What has been the uncritical evolution of the economic and social forms of the powerful has always been presented as a most desirable 'modernity'.

We should reflect deeply on the opportunities and the risks before us, risks that we share. No nation should ever be made to rush unthinkingly towards a model of development presented in the illusory guise of an ill-defined 'modernity', one that simply gives credence to what is a failed and pernicious paradigm.

Are current models of global trade and finance, production, resource extraction, models that truly advance the fundamental objective of human development?

Do such models protect the hierarchy of purpose that should exist - that must be restored - between morally purposeful economic and social outcomes? As to quantifying our achievements or failures, to what extent do economic growth rates, as are currently narrowly defined and measured, reflect the ability of our economies to respond to the basic needs of our most vulnerable citizens, provide universal basic services?

These are questions we must answer through the prism of our current circumstances, but now also within the new parameters of the global agreements that were secured in 2015 in relation to sustainable development and climate change the United Nations 2030 Agenda on which, alas, we are so off course; indeed in some areas we are even regressing.

We have a historic opportunity, and indeed duty, to lay the foundations of a new model for human flourishing and social harmony. We must confront the militaristic rhetoric that is now so omnipresent and even hegemonic.

The scale of the global challenges we face together requires not only a recovery of the genuinely idealistic impulses which drew our forefathers forward in their best and selfless moments towards a new world of independence. It also requires new paradigms for cooperation at national and international level, and also new scholarship, of such a nature as can generate balanced and respectful relationships between the peoples of the world, and between humans and the various forms of life on our shared planet.

Today, Ireland and Vietnam have emerged as countries on a path to greater flourishing, with a myriad of opportunities in sight for new international partnerships.

My hope for our deepening relationship, and I sense it is your hope too, President, is that we will manage, together, to build a cooperative, caring and non-exploitative civilisation, informed by the best of the traditions and institutions of the nations of the world, but also by the diversity of our collective experiences and memories - including those that will inevitably recall old wounds, failures and opportunities lost, but also visions invigorated and futures imagined and made real, perhaps even drawing on utopian ideals.

There is a growing young Irish population currently living in Vietnam, many working in the education sector - both gaining and sharing valuable experience. I thank you for the warm welcome they have received. That warm welcome is, I know, extended to the many Irish people who visit Vietnam each year to experience your incomparable landscapes and rich cultural heritage.

Here in Ireland, the Vietnamese community, is estimated at approximately 4,000 people. It is a thriving community that makes an important and valued contribution across many areas of national life - social, economic and cultural.

Our two countries share an appreciation of, and attachment to, culture, both traditional and contemporary. Our peoples place a high value on literature, poetry, music and song. I would like to warmly thank the musicians who have performed for us this evening.

Dear guests, celebrating all that we have been sharing and will share in friendship and ever closer relations assisted by this visit, may I now invite you all, distinguished guests, to stand and join me in a toast:

Wishing President To Lam good health and lasting friendship between the people of Ireland and Vietnam.

Beir beannacht do a Shoilse Uachtaran Vitneam agus muintir.